The Influence of Special Interests and Rentiers on Monetary and Fiscal Policy

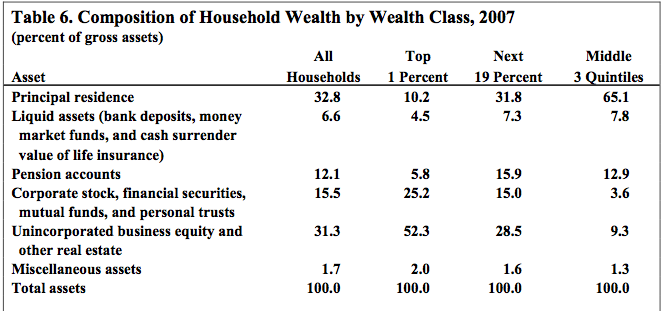

Triggered by Robert Kuttner’s column in the American Prospect, the explanation du jour of our current economic malaise blames the ‘rentier class’ i.e. owners of financial assets - the thesis being that wealthy Americans do not want any more inflationary policies to be enacted and may even prefer deflation instead. Paul Krugman argues that wealthy Americans do not want inflation because financial securities are overwhelmingly held by the richest 10% of the population. But what matters for the incentives of rich households is what proportion of their balance sheet is made up of nominal financial securities. And Edward Wolff’s paper shows us that a significant proportion of the balance sheet of wealthy Americans is made up of real assets - real estate, stock and business holdings.

Similarly, a return to deflation will result in a fall in demand for products and services sold by businesses and a deterioration in bank balance sheets with increased and disruptive bankruptcies. As Brad DeLong noted, no one benefits from a deflationary collapse in the economy. A much better explanation is offered by Matthew Yglesias when he observes that "the Fed has hardly been indifferent to the potential for monetary expansion. It’s just that the goal of monetary expansion has been to do just enough to stabilize financial asset prices without going far enough to produce catch-up growth in the labor market." What wealthy Americans, businesses and banks share is a common interest in supporting asset prices (real and nominal), a lack of interest in seeking full employment unless it is a prerequisite for supporting asset prices, and an aversion to any policies that can trigger wage inflation.

This bias towards asset price inflation doesn’t just impact the amount of stimulus. It has an influence on the type of stimulus that is preferred in this class conflict. The goal of asset price inflation without wage inflation is best achieved by an exclusive reliance on monetary policy - as I discussed in a previous post, a combination of “liquidity” facilities to prevent a collapse in shadow money supply and open market operations/QE to reduce real rates across the risk-free curve. Given the anaemic state of household balance sheets and insensitivity of corporate investment to interest rates due to a cronyist corporate sector, lower rates will not trigger sufficient real economic activity to trigger wage inflation but they will support real asset prices. Even within the ambit of fiscal policy, supply-side incentives for businesses are preferred. Given a less than competitive corporate sector, these will feed through to business profits more than they will feed through to wage inflation and employment.

Some of you may have noticed the distinctly Marxist tone of this debate - an emphasis on class conflict that rarely permeates economic discussion in mainstream circles. This is not a coincidence - as I observed in an earlier post, the dynamics of a crony capitalist economy resemble a zero-sum Marxian class struggle. Rather than expanding the size of the economic pie, economic agents focus their energies on trying to capture a larger slice of a static, stagnant output.

Comments

scepticus

I think the 'ineffectiveness of monetary policy in raising wages' is due to interest rate differentials globally. Certainly QE has been very effective IMO at raising wages, just not at raising them in America, since the savings ejected from nominal bonds goes overseas looking for yield. Imagine for the moment that there were little or no global interest rate differentials, or that sufficient capital controls on inflows are put place in the EMs, then I can't see how expansionary monetary policy could fail to raise wages.

Ashwin

In my view, reducing rates on the long end has very little impact on aggregate demand in the current economic situation. The consumer is too levered up and cannot increase consumption much. And business investment is just not sensitive enough to interest rates once they're already as low as they are. I should also point out that I don't really view the exchange of short-dated interest-bearing reserves for longer-dated govt bonds as having any impact on broad money supply except through the interest rate channel stimulating increased bank borrowing etc.

scepticus

The FED positions the purpose of QE as "moving investors out along the risk curve", which would work if the new investment they were to choose involved domestic workers. Then the investment would presumably involve some job creation, as opposed to a government bond which is just costing taxpayers money in interest payments. I agree that the mere swap of longer duration securities for shorter duration ones doesn't in itself accomplish anything very much either way vis-a-vis wages, except by reducing the government interest burden, and therefore possibly reduction of taxation. An unfunded tax cut for the lower paid would be more useful. Maybe that's next, because it is at least partially compatible with both right and left wing ideology.

Ashwin

An unfunded tax cut for the lower paid I could get behind - unfortunately I'm not as optimistic as you that we'll see it anytime soon!

Bruce Wilder

I would urge you to connect your May 12th post more closely with this one. Financial assets could shadow real business assets, using the cash-flows from production and sale of actual products and services, to fund the financial assets. That's a pretty picture. But, it cannot explain more than a fraction of the financial assets swirling around the U.S. economy. Intra-financial-sector debt creates financial assets that just cover for predation: "insurance" schemes that extract rents in the time-honored manner of loan sharks and ponzi artists everywhere. Deflation marks a phase-change that will cause the real economy to collapse. Inflation sets off a process causes real rates to fan out, and risks to be revealed. So we're stuck where we are, but even stability has its price in slow erosion. The U.S. is rapidly disinvesting in real business assets, under the cover of this darkness. Much of this is driven by technological obsolescence, and the order-of-magnitude reductions in capital requirements in various communication-and-control aspects of business production production processes. (This is most visible in publishing of books, music, newspapers, movies, software, and phone and broadcasting service provision). The price of the end-product/service remains hovering "in the air" after the superstructure of wages and other costs has been pulled away, more desperately dependent on gov't rules (e.g. IP law, utility regulation) then ever. Resumption of inflation and a more "normal" economy could result in relative collapse of prices and revenues in Media, tech and utility sectors (and a relative explosion, I suppose, in more tangible products, esp. food and fuel). Wages do not have a simple linear relation with other prices. If wages are falling, because capital (tools) are diminished by disinvestment, they will bring down some business sectors with them, as relative prices adjust. People will not be happy to see food prices rise, and they won't pay $11 to go to see a movie, which they can steal for nothing.

Ashwin

Bruce - again an excellent comment. On the point regarding financial assets, the main driver of this explosion is financial derivatives. Asset and liabilities can get created without limit in banking today that have nothing to do with the real economy, being simply side-bets. Slow erosion is a great way to put it - the current "low negative real rates" regime is a disequilibrium regime but it is one that can be maintained for a while. Although recent economic data suggests that I may have overestimated how long it can continue. When people compare it to the 50s, they ignore just how controlled the financial sector was then and just how "free" it is now. Minsky is excellent on this evolution. And there is no turning back without extinguishing half the contracts in the banking system, which will also most likely end in some form of collapse. The intersection of this narrative with the technological evolutionary narrative is important but I haven't got a clear view on what exactly it is. But the combination of a sclerotic and cronyist economy alongwith technological changes means that this disinvestment has been going on for a long time.

The Case Against Monetary Stimulus Via Asset Purchases at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] a transfer of wealth towards asset-holders and regressive in nature (financial assets are largely held by the rich). The very act of making private sector assets “safe” is a transfer of wealth [...]

The Distributional Consequences of Monetary Policy | Modern Monetary Realism

[...] a transfer of wealth towards asset-holders and regressive in nature (financial assets are largely held by the [...]

Helicopter Money Is Not Dangerous, All Macroeconomic Policy Is Dangerous at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] always, the conventional wisdom simply mirrors the interests of the 1%. It is considered “normal” to dole out favours to well-connected crony capitalists. It is [...]

House Prices, The Wealth Effect And Crony Capitalism at Macroeconomic Resilience

[...] I illustrated in a previous post, “a significant proportion of the balance sheet of wealthy Americans is made up of real assets [...]